Astronomers have detected an explosion of gamma rays that repeated several times over the course of a day, an event unlike anything ever witnessed before. The source of the powerful radiation was discovered to be outside our galaxy, its location pinpointed by the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT). Gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) are the most powerful explosions in the Universe, normally caused by the catastrophic destruction of stars. But no known scenario can completely explain this new GRB, whose true nature remains a mystery.

Munchen, September 09, 2025.- This GRB is “unlike any other seen in 50-years of GRB observations,” according to Antonio Martin-Carrillo, astronomer at University College Dublin, Ireland, and co-lead author of a study on this signal recently published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

GRBs are the most energetic explosions in the Universe. They are produced in catastrophic events like massive stars dying in powerful blasts or being ripped apart by black holes, among other events. They usually last milliseconds to minutes, but this signal — GRB 250702B [1] — lasted about a day. «This is 100-1000 times longer than most GRBs,” says Andrew Levan, astronomer at Radboud University, The Netherlands, and co-lead author of the study.

“More importantly, gamma-ray bursts never repeat since the event that produces them is catastrophic,” says Martin-Carrillo. The initial alert about this GRB came on 2 July from NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. Fermi detected not one but three bursts from this source over the course of several hours. Retrospectively, it was also discovered that the source had been active almost a day earlier, as seen by the Einstein Probe, an X-ray space telescope mission by the Chinese Academy of Sciences with the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics. Such a long and repeating GRB has never been seen before.

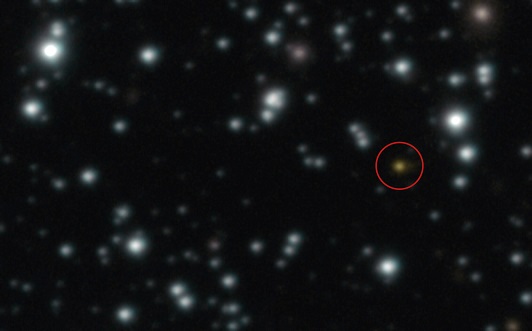

These observations only provided an approximate location for the GRB, which was towards the plane of our galaxy, crowded with stars. Therefore, the team turned to ESO’s VLT to pinpoint the actual source within this area. “Before these observations, the general feeling in the community was that this GRB must have originated from within our galaxy. The VLT fundamentally changed that paradigm,” says Levan, who is also affiliated with the University of Warwick, UK.

Using the VLT’s HAWK-I camera, they found evidence that the source may actually reside in another galaxy. This was later confirmed by the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. “What we found was considerably more exciting: the fact that this object is extragalactic means that it is considerably more powerful,” says Martin-Carrillo. The size and brightness of the host galaxy suggest it may be located a few billion light-years away, but more data are needed to refine this distance.

The nature of the event that caused this GRB is still unknown. One possible scenario is a massive star collapsing onto itself, releasing vast amounts of energy in the process. “If this is a massive star, it is a collapse unlike anything we have ever witnessed before,” says Levan, as in that case the GRB would have lasted just a few seconds. Alternatively, a star being ripped apart by a black hole could produce a day-long GRB, but to explain other properties of the explosion would require an unusual star being destroyed by an even more unusual black hole. [2]

To learn more about this GRB, the team has been monitoring the aftermath of the explosion with different telescopes and instruments, including the VLT’s X-shooter spectrograph and the James Webb Space Telescope, a joint project of NASA, ESA and the Canadian Space Agency. Finding that this explosion took place in another galaxy will be key to deciphering what caused it. “We are still not sure what produced this, but with this research we have made a huge step forward towards understanding this extremely unusual and exciting object,” says Martin-Carrillo.

Notes

[1] Also known as GRB 250702BDE. GRBs are named with a number denoting the date when they were detected, followed by a letter if more than one burst was found that day. Bursts B, D and E are all linked to the same object.

[2] The authors favour a scenario in which a white dwarf was shredded by a so-called intermediate-mass black hole. A white dwarf is the small, slowly-cooling core that is left behind after a star like our Sun dies. Intermediate-mass black holes are between 100 and 100 000 times more massive than the Sun. Most known black holes have masses significantly greater or lower than that, and intermediate-mass black holes remain a poorly understood type of object.